Emergency Imaging of Brain Tumors

You can learn more about brain tumors on the brain tumor topic page. Also, please check out our full channel on Youtube.

Tag: Medical students

Pages geared towards the education level of a medical student.

You can learn more about brain tumors on the brain tumor topic page. Also, please check out our full channel on Youtube.

This video is an overview from Dr. Katie Bailey about fractures of the face, including their CT findings and complications. Facial fractures are among the most commonly encountered emergencies, particularly in busy trauma hospitals.

Simple fractures. These involve isolated fractures of one of the sinus walls, the zygomatic arch, or the nasal bones.

Frontal sinus fractures. Consider whether they involve the outer table, inner table, or both. Complications of frontal sinus fractures include CSF leak, mucocele, or meningitis. Brain parenchymal contusions can also accompany frontal sinus fractures.

Other common isolated fractures. Common fractures include the zygomatic arch and mandible. When you have a fracture of the mandible, it is very common to have a fracture elsewhere in the mandibular ring. Nasal fractures are commonly seen and are worse if there is displacement because they can result in poor cosmetic outcomes. Nasal septal fractures are sometimes challenging to see and soft tissue swelling is probably your best clue. A nasal septal hematoma, if present, can result in necrosis of the nasal septum.

Lamina papyracea fractures. These are fractures of the medial wall of the orbit. Most commonly, these result from a blow to the eye. Soft tissue swelling within the orbit or blood in the sinus can tell you if you are likely dealing with a more acute fracture. A retroorbital hematoma can accompany these fractures, and are characterized by stranding or soft tissue density in the retroorbital fat. These require more rapid intervention to avoid risks to vision

Orbital floor fractures. These can have displacement of fragments into the adjacent maxillary sinus, and it is important to report if the muscles are displaced into the sinus. Entrapment of the muscle can result in loss of eye movement and may need to be managed surgically.

Single sinus fractures. Sometimes you will have a fracture of only a single sinus, often from a direct blow. These can involve one or more walls of the sinus. Sphenoid sinus fractures can be complicated by extension into the carotid canal which increases the risk of vascular injury.

Lefort fractures. Lefort fractures involve the pterygoid plates and are subdivided into 3 types. They can be unilateral or bilateral. Lefort I fractures extend through the inferior maxilla and not the roof of the sinus. This is a transverse pattern which is low across the maxillary sinus. Lefort 2 fracture extend through the inferior lateral maxilla but extend superiorly as they go medially through the midface and inferior orbital wall. A Lefort III fracture is a transvere fracture which is higher and goes through the lateral orbital wall and potentially the zygoma.

ZMC fractures. These are fractures of the zygomaticomaxillary complex. They involve the struts of the zygoma, including the anterior maxillary wall, posterior maxillary wall, zygoma, and frontal sinus.

NOE fractures. Nasal-orbital ethmoidal fractures are a pattern of injury etending from the nasal bones through the septum, ethmoid sinuses, and medial orbital walls across the bridge of the nose. These can cause injury to the nasolacrimal duct or medial canthus, reducing eye movement.

Hopefully you learned a bit from this video about how to categorize facial fractures on CT. Be sure to check out the other videos on search patterns as well as all the other head and neck topics.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey gives us an overview of how to approach a CT of the sinuses, including an overview of anatomy, some common pathology, and red flags to look out for as you interpret the images.

Overview of sinus anatomy. There are 4 main sinuses, the maxillary, ethmoid, sphenoid, and frontal, which are both paired. The nasal cavity and orbits are also important structures to discuss.

Maxillary sinus. When evaluating the maxillary sinus, you should describe whether there is opacification, the appearance of the bony walls, and the outflow tract (the ostiomeatal complex).

Frontal sinus. The paired frontal sinuses should also be described in terms of aeration and bony walls. They drain through the frontoethmoid recess into the anterior ethmoid air cells.

Ethmoid air cells. There are anterior and posterior ethmoid air cells which can have mucosal thickening or opacification. The Haller cell is an important variant in which an ethmoid cell is found below the medial orbit that can contribute to obstruction. Ethmoid sinusitis can extend into the orbits and cause orbital cellulitis, an important complication.

Sphenoid sinus. The sphenoid sinus is posterior to the ethmoids and may have a fluid level, as it is a dependent sinus. The drainage is into the posterior ethmoids via the sphenoethmoid recess. Adjacent structures including the sella, internal carotid artery, and clivus can all be affected by sphenoid sinus disease.

Nasal cavity. Important features of the nasal cavity are the nasal septum, turbinates, and any potential polyps. An important variant is the concha bullosa, which is an aerated middle turbinate, which can contribute to sinus outflow obstruction.

Anatomic variants. Important anatomic variants can affect the optic canal, such as absence of the bone. The olfactory fossa can also have variants where the depth is greater or less. Keros is a classification used to describe how deep the olfactory fossa is. The vidian canal contains the vidian nerve and is best seen on the coronal images just above the pterygoid plates. It can be medially directed and run in the wall of the sphenoid sinus, which exposes it to injury. The carotid canal can be medially positioned and very close to the sphenoid sinus, also putting it at risk of injury. There are variants in the sphenoid septa, in which it attaches along one lateral wall rather than in the midline.

Red flags of sinus imaging. Abnormal soft tissue or stranding in the retromaxillary fat or pterygopalatine fossa is an important red flag which can signal invasive (possibly fungal) sinusitis. Similarly, stranding in the orbit can raise the possibility of invasive sinusitis. Another red flag is bony disruption, particularly along the sinus walls or in the nasal cavity.

Conclusion. Don’t forget to look at other things in the images, including the brain, sella, nasopharynx, mandible, teeth, orbits, and more.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on the internal auditory canal. Be sure to check out the additional videos on other

head and neck topics.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey talks about the imaging findings of pulsatile tinnitus. Pulsatile tinnitus is a ringing or abnormal sound sensation in the ear, but unlike the most common high frequency tinnitus, it has a pulsatile or wavelike quality that can often oscillate with arterial or venous flow. Causes of pulsatile tinnitus are unique and a different approach is warranted.

General approach and common causes. Some findings are best seen on CT and others are best seen on MRI. For this reason, you can often perform either a CT or MRI when you begin. There are a wide range of possible causes that can be categorized into neoplasm, arterial, and venous.

Paragangliomas. Glomus tympanicum, or tympanicum paraganglioma, is the most common middle ear tumor. These are more common in women than men. The most common location is along the floor of the middle ear adjacent to the cochlea. A glomus tympanicojugulare has features of both a jugular paraganglioma and tympanic paraganglioma, often connecting them. On MRI, these appear as permeative masses with bone destruction and enhancement.

Vestibular schwannoma is the most common tumor of the internal auditory canal and usually arise from the inferior vestibular nerve. These are solidly enhancing masses that extend from the IAC into the cerebellopontine angle.

Other tumors that can occur in or around the region include meningiomas and chondrosarcomas. Meningiomas are usually homogeneously enhancing and may have dural tails. Chondrosarcomas are often centered around the petroclival junction.

Arterial anomalies can also cause pulsatile tinnitus. If the internal carotid artery extends into the middle ear with no bony covering, this is an aberrant ICA. A persistent stapedial artery can also cause pulsatile tinnitus. The absence of foramen spinosum suggests a variant with no middle meningeal artery and a persistent stapedial artery.

Other vascular causes include vascular loops and microvascular compression of the nerves in the IAC. These can also cause pulsatile tinnitus, although the role of an AICA loop has been controversial. Other carotid abnormalities such as carotid stenosis, dissection, or fibromuscular dysplasia are also associated with tinnitus.Hemangiomas, or encapsulated venous vascular malformations, are benign vascular malformations which have high flow

Venous abnormalities can also cause tinnitus. These may be a more constant tinnitus or hum with less arterial type pulsation. Absence of the bony wall around the jugular bulb is known as a dehiscent jugular bulb. Venous diverticula from the sigmoid sinus or jugular vein are small outpouchings of the vein, almost like aneurysms. Other vascular malformations such as dural AV fistulas and arteriovenous malformations can cause tinnitus, and can be confirmed on vascular imaging studies. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension causes stenosis of the lateral transverse sinuses which can also cause tinnitus.

A few other things can cause pulsatile tinnitus, such as cotospongiosis/otosclerosis and Paget disease.

Overall, a number of things can cause pulsatile tinnitus, but a few of these things are more common so you should keep your eye out for them.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on the internal auditory canal. Be sure to check out the additional videos on other

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey describes the internal auditory canal including the anatomy and some of the common pathology that you may encounter.

Review of internal auditory canal (IAC) anatomy. The IAC includes arteries and nerves. The most easily seen structures are the facial (cranial nerve VII) and vestibulocochlear (cranial nerve VIII) nerves. On a sagittal view, the anterior portion of the canal contains the facial nerve (superior) and cochlear nerve (inferior). This can be remembered by the mnemonic “7up, Coke down”. The oropharynx includes the tonsils (both lingual and palatine), the squamous mucosa of the pharynx, the uvula, and the vallecula. oral cavity includes the lips, teeth, hard and soft palate, gingiva, retromolar trigone, the buccal mucosa, and anterior 2/3 of the tongue. Masticator space. Contains the muscles of mastication, the mandible, branches of the trigeminal nerve, lymph nodes, and minor salivary glands.

Vascular loop. Sometimes an arterial branch can compress the nerves as they enter the IAC. If you see mass effect, this is particularly possible. Smaller loops of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery are more controversial but has been previously described as associated with hemifacial spasm. If you see it, you can be descriptive about which portion of the nerve is involved.

Vascular malformations are a rare cause of symptoms, but if you see an unusual tangle or cluster of vessels in the region you should

Vestibular schwannomas are the most common tumor affecting the IAC. They usually arise from the inferior vestibular nerve, and have previously been referred to as “acoustic neuromas”. With these tumors, you will see an enhancing mass with pretty homogeneous enhancement centered in the IAC with extension into the porus acousticus. They can sometimes be quite small but still symptomatic.

Meningiomas are the second most common solid mass. They are also solid enhancing masses near the IAC. Key clues that they are not schwannomas are a center outside of the IAC. Dural tails, or linear areas of tumor tracking along the dura, can be helpful, but schwannomas can also have them.

Epidermoids are relatively uncommon non-enhancing masses of the CP angle and IAC. They look cystic on T2 and can be close to CSF, but their key distinguishing feature is hyperintensity on DWI.

Bell’s Palsy is an idiopathic facial paralysis on one side. Imaging can often be normal, but if you see linear enhancement in the distal auditory canal this can be a sign of Bell’s palsy. The geniculate and mastoid portions of the facial nerve can enhance in normal cases, so in those cases you must consider the symmetry.

Red flags in the IAC include nodular enhancement and multiple cranial nerves enhancing. This should make you think of unusual pathology such as lymphoma, sarcoidosis, metastatic disease, perineural spread of tumor, and Lyme disease.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on the internal auditory canal. Be sure to check out the additional videos on other head and neck topics.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey describes her approach to imaging of the orbit with a focus on common diseases that can affect the orbits. We’ll save neoplasms for another video and focus on other pathologies here.

Review of the anatomy of the orbits. The orbits are surrounded by orbital walls and contain the globes, extraocular muscles, nerves including the optic nerve, a variety of vessels and nerves, and the lacrimal gland.

The globes. Common pathologies involving the globes include ocular lens surgery/removal, retinal detachment and vitreous hemorrhage, and phthisis bulbi (a chronically shrunken and deformed injured globe). MRI is even better at seeing these pathologies and can see tumors within the globe, such as ocular melanoma.

The orbital walls. The most common pathology of the orbital walls are fractures, commonly of the medial or inferior orbital wall. Other common pathologies include invasion of sinusitis into the orbit or carcinoma invading the orbit.

Extraocular muscles. Thyroid orbitopathy often causes symmetric enlargement of the extraocular muscles. IgG related disease and lymphoma can also infiltrate the extraocular muscles. Of these, lymphoma and metastatic disease tend to be more masslike and well defined.

Optic nerve, disc, and sheath. The most common pathology is optic neuritis, which affects the nerve itself. This is common in demyelinating disease. Perineuritis is when the enhancement/inflammation is around the nerve and has a different differential diagnosis. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) can cause distended and tortuous optic nerve sheaths as well as elevation of the optic disc (papilledema).

Vessels. The ophthalmic artery is the most visible vein and often can have aneurysms. The superior ophthalmic vein is the largest vessel, and can have varices or thrombosis (often in the setting of infection).

Retroorbital fat. The fat is important because it can be a sign that other structures are abnormal. This is most commonly abnormal in orbital cellulitis, but can also be abnormal if there is a hematoma or orbital inflammatory disease.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on orbital imaging and common non-neoplastic pathology. Be sure to check out the additional videos on other head and neck topics.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

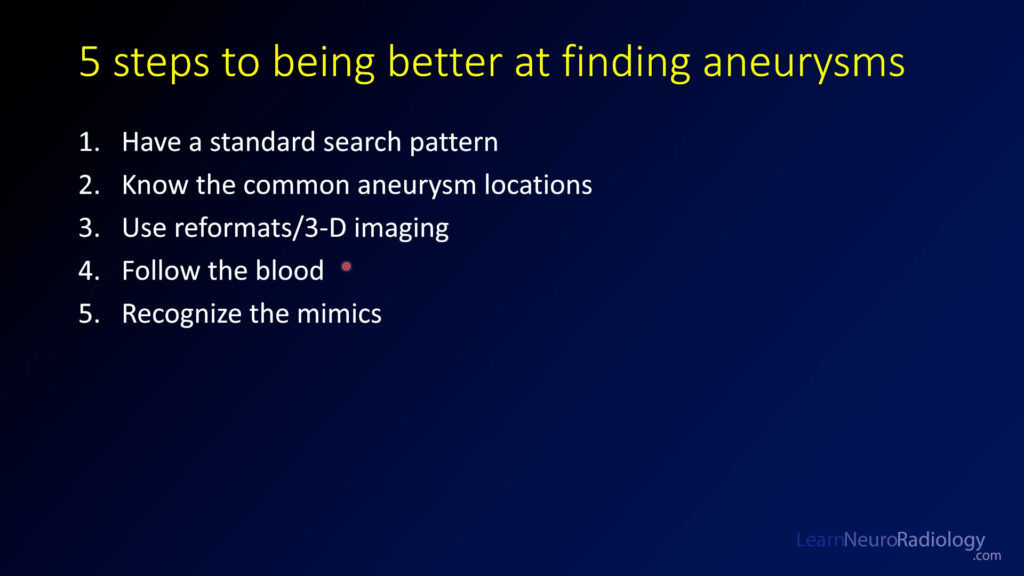

In this video, I walk you through 5 quick tips that you might use to improve your brain aneurysm search pattern on CT angiograms of the brain. This is a longer version of a lecture I put together with Everlight Radiology, so be sure to check them out.

Have a standard search pattern. When I’m looking at a CTA of the head, I do the anterior circulation first and then move from right to left, then over to the posterior circulation.

Know the common aneurysm locations. The most common aneurysm location is the anterior communicating artery (35%) followed by the carotid terminus (30%) and middle cerebral artery (20%). Posterior circulation aneurysms are relatively uncommon (10%) but it’s important to look there as well. Try to use these tips on the sample case.

Use reformats and 3-D imaging. These supplemental tools can help you improve your sensitivity. Multiplanar reformats are thin slices that are displayed in the other planes, while maximum intensity projections (or MIPs) show you the brightest pixel in a thicker slice. Volume renderings are a nice way to make measurements and increase your sensitivity.

Using the MIPs can definitely make you more sensitive. The axial MIPS are great to see the MCAs, the sagittal MIPs are great to see the carotid terminus and ACAs, and the coronal MIPs are great to see the posterior circulation and MCAs again.

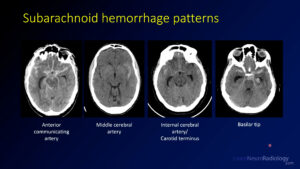

Follow the blood. This is my favorite tip. The location of the blood on the non-contrast CT is one of the best clues about where your aneurysm is going to be. You need to check that area very closely.

Recognize the mimics. There are some things which can mimic aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage, but some features may help you know that it is less likely to be from an aneurysm. Atypical location, an unusual history, or unusual patient demographics can clue you in that it might be a different cause. Be sure to think about hypertensive hemorrhage, venous infarct, tumor (glioma, metastasis, or cavernous malformation), and benign perimesencephalic hemorrhage.

Summary. These 5 quick tips can help you be better at understanding aneurysms and being better and finding them.

If you haven’t already, be sure to check out the vascular imaging course and sample cases that you can scroll through.

See all of the search pattern videos on the Search Pattern Playlist.

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey walks us through cancers of the larynx and quickly describes how they are staged. This quick video will help you identify common laryngeal cancers and how to stage them.

Review of the anatomy of the larynx. The larynx consists of structures from the inferior aspect of the epiglottis down to the inferior part of the cricoid cartilage. There are three subsites, the supraglottis (between the epiglottis and the false cords), the glottis (the true vocal cords, anterior commissure, and posterior commissure), and subglottis (from the inferior vocal cords to the inferior cricoid cartilage). Key landmarks include the aryepiglottic folds, the pyriform sinus, the false cords, the true cords, the arytenoid cartilage, and the cricoid cartilage.

Laryngeal cancer staging is based on a T, N, M stage. Supraglottic cancers and glottic cancers are staged separately. For supraglottic cancers, it is important to know if the vocal cord is mobile or fixed, which can only be determined on exam. T4B tumors are unresectable because they involve adjacent structures such as the prevertebral space or carotid artery. Glottic cancers are staged based on their involvement of adjacent structures. Similarly unresectable tumors involve deep adjacent structures.

Example case 1. This case has thickening and nodularity of the right aryepiglottic fold. This is confined to the aryepiglottic fold with no involvement of adjacent structures. There are no nodes, making this a T1N0 tumor.

Example case 2. There is a subtle tumor along the anterior aspect of the right vocal cord with asymmetric hyperdensity. This is a glottic lesion involving only the right vocal cord with no nodes, consistent with a T1N0 glottic tumor.

Example case 3. This is a more dramatic mass involving the right vocal cord with erosion of the cricoid cartilage posteriorly and loss of paraglottic fat. There is supraglottic and glottic extension. This is a T3N0 lesion.

Example case 4. To see this lesion, you have to window the images pretty severely. There is hyperdensity involving the anterior commissure and both anterior vocal cords. The involvement of both vocal cords makes this a T1bN0 lesion.

Example case 5. This bulky mass extends across the anterior commissure and extends through both sides of the thyroid cartilage. Destruction of the cartilage makes this a T4a lesion. Left level 3 lymph node is abnormal, making this an N1 nodal stage.

Conclusion. Hopefully you learned from these examples of supraglottic and glottic tumors and can use some of your skills on your future cases.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on nasopharyngeal cancer staging. Be sure to tune back in for additional videos on staging of the other head and neck subsites.Also take a look at the head and neck topic page as well as all the head and neck videos on the site.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey takes us quickly through the nasopharynx, a common location of malignancies in the head and neck, and walks us through some quick samples of how they are staged.

Review of the anatomy of the nasopharynx. The nasopharynx is behind the palate and includes the clivus. The nasopharynx is largely lined by squamous mucosa with lymphoid tissues and muscles. An important landmark is the torus tubarius and fossa of Rosenmuller.

Nasopharyngeal cancer staging, like other subsites, is based on a T, N, M stage. Nasopharyngeal cancers are predominantly staged based on whether adjacent structures, such as surrounding soft tissues or the skull base, are involved. Unlike the other tumor sites, size is not involved in the T staging.

Example case 1. There is a soft tissue mass filling the nasopharynx, asymmetrically larger on the right. Erosion of the adjacent bony structures, including the clivus, are important. The tumor is extending into the sphenoid sinus. Involvement of the bony structures and sinuses makes this is a T3 tumor, and there were no nodes or distant metastases (not shown).

There is a more subtle example of bone erosion of the posterior wall of the sphenoid sinus and left carotid canal along with the clivus.

Example case 2. There is a soft tissue mass eroding the petrous apex and left aspect of the clivus. MRI better shows the extent of the involvement, where you can see that there is intracranial involvement into Meckel’s cave (trigeminal foramen). The intracranial involvement makes this a T4 tumor. There were no nodes or distant metastases (not shown).

Example case 3. In this case, there are necrotic lymph nodes in the parapharyngeal and prevertebral space as well as extending down the neck at multiple internal jugular levels. The original CT did not show a mass in the nasopharynx, but because of the nodes, a nasopharyngeal cancer is suspected. The PET/CT is able to locate the abnormality along the left torus tubarius. The local nature of this tumor makes it T1, but the bilateral lymph nodes make it an N3 for nodes.

Extra case. An incidental polypoid mass is seen in the left nasopharynx on a brain MRI with minimal peripheral enhancement and central reduced diffusion. The homogeneously low T2 appearance and reduced diffusion make this suspicious for lymphoma, although you would not be able to tell until this lesion had been biopsied.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on nasopharyngeal cancer staging. Be sure to tune back in for additional videos on staging of the other head and neck subsites.Also take a look at the head and neck topic page as well as all the head and neck videos on the site.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel

revised 11/12/2022

N.B. The initial version of this video had a few small errors in the staging, so we have corrected them.

In this video, Dr. Katie Bailey describes the anatomic subsites of the oropharynx and reviews how tumors are staged through four quick example cases.

Review of oropharynx anatomy. The oropharynx includes the tonsils (both lingual and palatine), the squamous mucosa of the pharynx, the uvula, and the vallecula. oral cavity includes the lips, teeth, hard and soft palate, gingiva, retromolar trigone, the buccal mucosa, and anterior 2/3 of the tongue. The masticator space contains the muscles of mastication, the mandible, branches of the trigeminal nerve, lymph nodes, and minor salivary glands.

Oropharyngeal cancer staging. Tumor (T) staging is based on the size of the tumor or invasion through adjacent structures. Nodal (N) staging is based on the number, location, and size of nodes, and metastasis (M) staging is based on the presence or absence of distant sites of disease.

Example case 1. There is a 2.4 cm mass of the right palatine tonsil. There is level 2 and 3 adenopathy. The lymphadenopathy compresses the jugular vein and displaces the adjacent sternocleidomastoid. The size of the tumor makes this a T2 lesion, and the unilateral adenopathy less than 6 cm with multiple nodes makes it N2b. Because metastases can’t be evaluated with this information, it is given an ‘X’ for M staging right now.

Example case 2. There is a 3.2 cm mass in the tongue base and extending into the vallecula. There is no extension into the adjacent structures or fat. There is a single left sided level 2 lymph node that is somewhat prominent but isn’t definitely abnormal. That makes this a T2N0Mx tumor. If a PET or biopsy later shows that the node is positive, the staging can be changed.

Example case 3. There is a subtle mass of the right lateral wall of the oropharynx involving the tonsillar pillar and tongue base. This one is quite hard to see. There are cystic necrotic lymph nodes on the right, but none greater than 6 cm. A PET/CT showed no distant metastatic disease. That makes this a T1N2bM0 tumor.

Example case 4. This patient presented with cervical lymphadenopathy on the left but had no clear primary tumor in the oropharynx. There was no mass of the tongue base or elsewhere. The patient had a lung node suspicious for metastatic disease. A PET/CT showed that there was a primary in the soft palate. The mass was detected only by PET/CT. The final staging for this cancer is T1N2bM1.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on oropharyngeal cancer staging.

Thanks for checking out this quick video on oral cavity cancer staging. Be sure to tune back in for additional videos on staging of the other head and neck subsites. Also take a look at the head and neck topic page as well as all the head and neck videos on the site.

See this and other videos on our Youtube channel